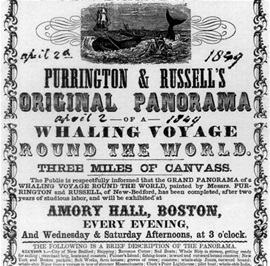

A broadside for a performance in April of 1849 at Armory Hall in Boston. Image from Wikipedia.

A broadside for a performance in April of 1849 at Armory Hall in Boston. Image from Wikipedia.

As a maker/performer of crankies, I am natually interested in how the scroll was made, cranked and performed. Here are a few facts along with my ponderings.

The scroll was painted with water-based, distemper paint on cotton sheeting. It measures 1,275' in length and 8.5' in height making it the longest surviving moving

panorama from that era. A few sections of the painting were revised/painted over by the artist. Revisions were not uncommon in those days. Once the artist saw the moving panorama being cranked from a distance, he might have thought of things he

wanted to change. Or, after performing the panorama, he might have gotten more ideas based on the audience's reactions.

Years of wear and tear took a toll on the painting. The paint

was flaking off in some sections, leaving some of the original artwork exposed. The museum made the decision to leave it alone so that we could see a bit of the editing process. Thank you!

Performance - It was noted in one 19th century review, that the performance was two hours long. Due to the immense length of the painting, it needed to be divided into four

spools. This meant that there had to have been three intermissions during the show to change spools. It made me wonder what happened during these breaks? Did the audience get up and move around? Or, was there music or additional entertainment

during the spool changes? And how long did it take the crew to change one of the huge spools? (Changing a moving panorama spool from the

Pilgrim's Progress panorama, 2015.)

Captain Daniel McKenzie, who had experienced 8 whaling voyages all over the world, was hired to narrate. No doubt, he was able to add fantastic personal

stories.

There might have been special lighting and sound effects during the storm scene. Use of hand-cranked wind machines, thunder

sheets and rain boxes were commonly used in moving panorama shows of that time.

Cranking - Most all moving panoramas

were cranked from left to right, but this one is unusual in that it was cranked from right to left. The artists cared about accuracy. Cranking right to left followed the route of the ship if one was traveling out of the harbor of New Bedford.

The crankist stayed behind the painting during the performance, hidden from view. Sometimes, the artist put symbols or words on the back of the painting to signal the crankist when to stop or start cranking.

I did inquire about any marks on the back of the painting and there are none. It made me wonder how the narrator communicated stopping, slowing down or speeding up to the crankist? Sometimes a code of coughs and a stamp of the foot were used (as written about by Mark Twain).

Travel was a challenge back in those days. The crew would have used

horse and cart, train and maybe steamboat. They would need to keep the immense spools secure and protected from wind and rain. Not an easy task as written about by another moving panorama showman in An Exhibitor's Diary.